Why the value of research is so hard to measure and what to do about it

How to show your worth when you create value through communication, not building things.

Research teams are stuck in an awkward place: they are meant to be a value creator rather than cost centre, but their impact is hard to measure. This often puts them in an uncomfortable and vulnerable position in their organisation.

If the CFO starts asking questions about “why are we spending £1 million a year on this UX research team?” then you need to have a good answer.

Problem 1: intangability

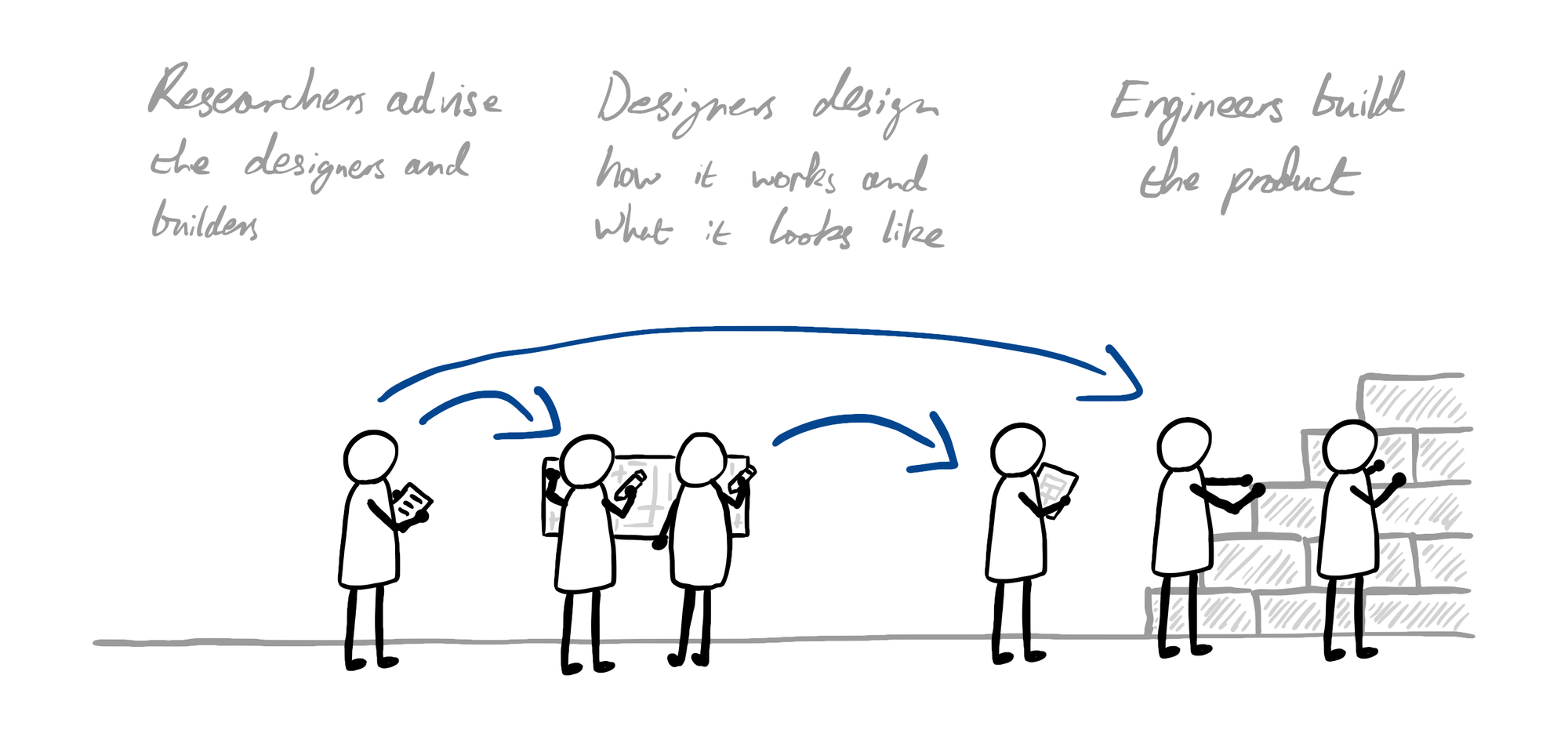

The fundamental challenge is that the value of research is only ever realised through communication. Researchers don’t build the product – they advise and influence the people who do.

There’s often no direct line from research spend to product outcome. You can’t point to a feature and say ‘research built that’ in the same way engineering can.

Instead, your medium for generating value is persuasion: helping designers, product managers and stakeholders make better decisions because of what you know. The goal of a researcher isn’t to ‘do the research’. It’s to use what they’ve learned about customers to change how other people think and act. This is why researchers need to think like marketers and a viral video is one of the highest forms of research impact.

Communication and storytelling aren’t nice-to-have soft skills for researchers. They are the job. You can discover the most brilliant insight in the world, but if you can’t persuade anyone to act on it, all you’ve done is cost the business money.

Problem 2: timing

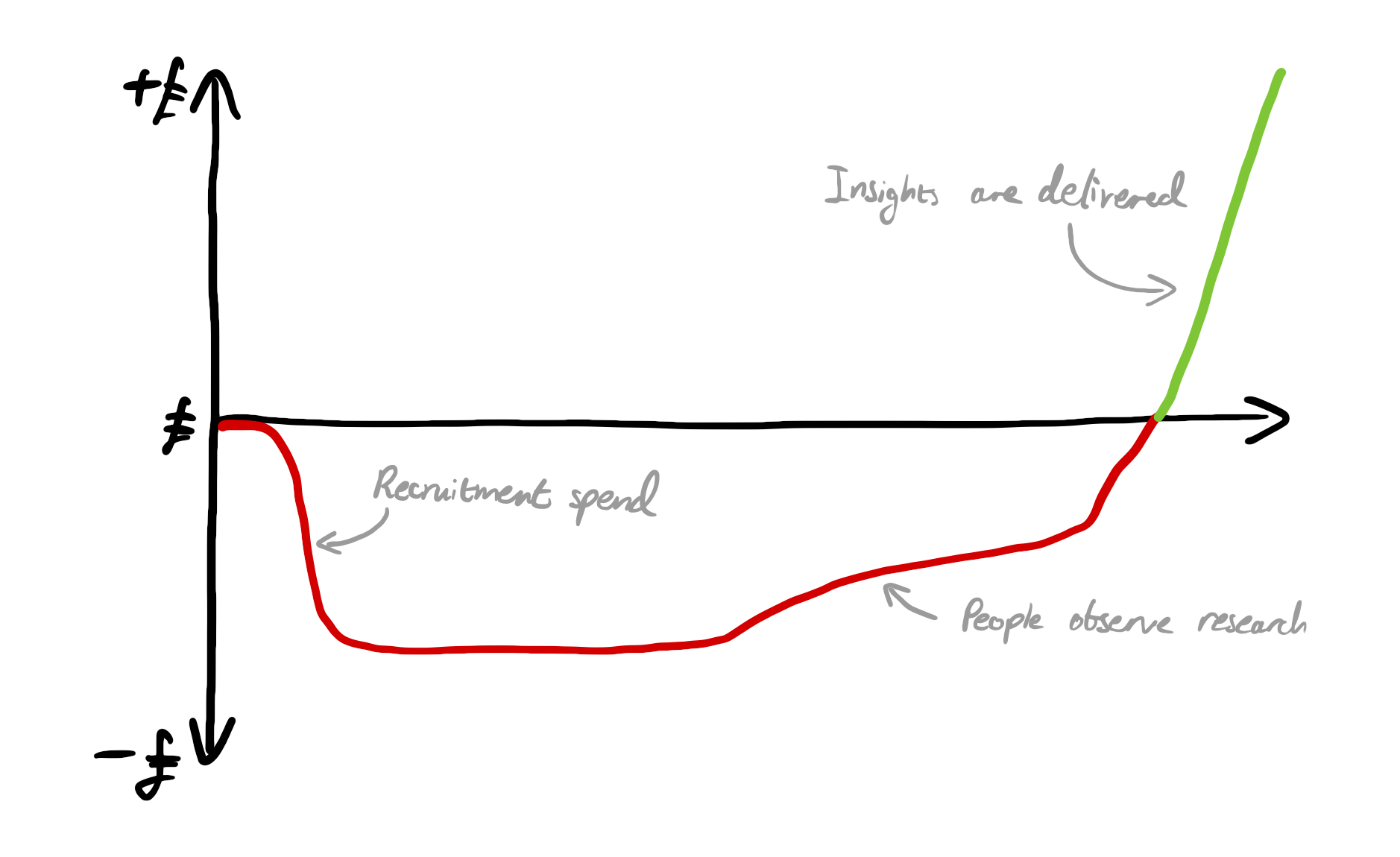

Thinking about research at a purely project level, it front-loads cost and back-loads value, so the business is effectively investing for weeks before seeing any return.

At the start of a project, while you’re recruiting, planning and conducting sessions, the business is spending money with little tangible to show for it.

Some value trickles in if stakeholders watch sessions live and start seeing things differently. But most of the value is delivered right at the end, when you present your findings and recommendations. That final moment carries disproportionate weight and it only works if people listen, pay attention and do something with what you’ve told them.

How to maximise and extend the value of research

If value is primarily created through communication and influence, then research teams need to think carefully about how to maximise it:

- Invest in storytelling and presentation as core craft skills. Focus on the craft of communicating insights to make sure they land. Don’t take it for granted that everyone in the team is already 10/10 on this. These skills deserve the same (if not more) attention as research tools and methods.

- Build long-tail artefacts. Personas, journey maps, design principles, insight repositories and other artefacts that people can refer to over time generate value over time. This is a research team’s ‘passive income’ which turns a one-off project into a long-term asset.

- Close the loop. Follow up with stakeholders a few weeks after a release to find out what shifted. Track which artefacts get reused and by whom. Keep a simple log linking your recommendations to the product decisions they influenced.

- Develop a system for capturing stories. Research leaders need to own the collection of stories about how research has impacted the product or service. Building a library of insights and examples of value the team has generated is one of the most important things a research leader can do.

There are also ways to increase the value that a research team can create:

- Draw on multiple data sources. If you’re primarily doing qualitative research, there’s only so much value you can generate. Combine it with data analysis, secondary research, competitor analysis and other methods and you’ll have more insights to work with and more opportunities to create value.

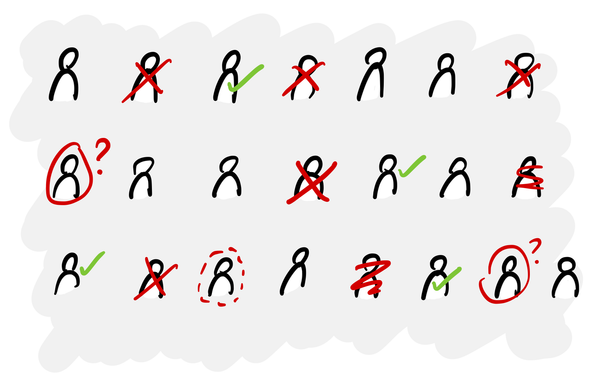

- Enable others through democratisation. Supporting designers and product managers to conduct their own research allows you to generate a lot of value from relatively few hours of your team’s time.

- Broaden the role beyond research. AI’s impact on coding means that the future of research is product discovery. Get your researchers involved in concept generation and prototyping, especially now that AI tools make this more accessible than ever. The closer a researcher gets to the making of the product, the less their value depends on persuading someone else to act.

By thinking about a research team in a purely commercial and transactional way, we can make sure that we’re delivering enough value to the organisation to justify its existence.

Why researchers resist this framing

This line of thinking doesn’t sit well with a lot of people. A research team isn’t a business. We shouldn’t be so focused on ROI. If you need to explain why we’re here, you’re doing it wrong!

Many researchers came into the field because they care deeply about understanding and advocating for people. They see their work as inherently valuable, self-evidently so. So when they’re asked to quantify impact or ‘sell’ their findings, it can feel like the organisation is questioning the premise of their discipline.

There are a few objections that you see:

- It feels reductive. Researchers deal in nuance, context and human complexity. Being asked to boil that down to ‘we saved £x’ can feel like it strips the richness and greater meaning out of the work.

- It feels like it shouldn’t be necessary. Researchers often look at designers or engineers and think that those roles don’t have to justify their existence in the same way. Whether or not that’s true, the perception can create resentment.

- It conflates advocacy with self-promotion. Researchers are trained to let evidence speak for itself. Having to actively campaign for attention feels uncomfortably close to marketing, which sits awkwardly with a discipline rooted in objectivity and rigour.

But the way to reframe it is that collecting evidence of impact isn’t proving your worth to sceptics. It’s closing the loop on your own work. If you genuinely care about customers, you should care whether or not your insights actually changed anything.

Researchers already know how to gather evidence, find patterns and build a compelling case from data. The final step is to turn those same skills inward and treat impact tracking as the last stage of the research process, not a bureaucratic chore.

The research leader’s role

Individual contributors have a big part to play in all of this, but it’s the research leader who owns the success or failure of the team. Thinking about their team in a purely commercial way doesn’t come naturally to many research leaders, whose background rarely prepares them for this. Yet it’s their job to ensure that the team generates as much value as possible for the organisation and that this is documented.

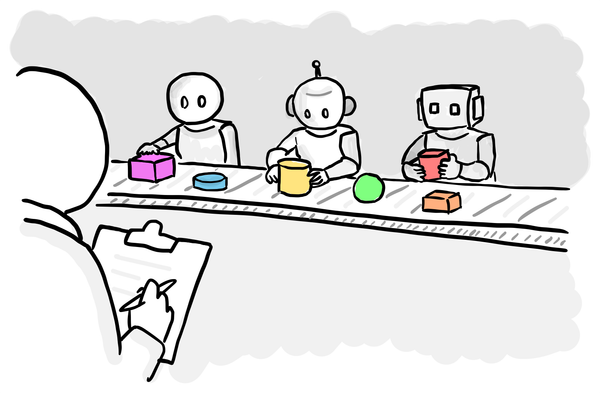

By thinking about their team as a system for generating value, they can make sure that all the parts are working as they should:

- Insights are being captured about things that the organisation cares about.

- What they learn is communicated effectively, so people listen and make better decisions.

- Artefacts are created to extend the lifespan of insights.

- The impact of the work is captured systematically through persuasive stories and hard metrics.

- Researchers are finding new ways to gather insights and contribute to the building of the product.

When a research leader builds this kind of system, it does more than prepare you for the CFO’s questions. It can change how the team feels about its own work.

Research is an anxious place to be right now. But when tracking impact is part of how you operate, people stop worrying about whether they can justify their existence because the evidence is there for everyone to see.