How vibe engineering will turn the product design process (and tooling) upside down

UX folk can look forward to building products, not just drawing pictures of them.

The primary impact of AI on product design will come from how coding agents are being used in production, rather than improvements in prototyping and design tooling.

Here’s my thesis:

- AI coding agents can now write 100% of production code

- This allows products to be built much faster

- But to create the front-end UI in code, you need a design system in code

- Getting a design system from Figma into code is currently a slow process

- Therefore it makes more sense to start production design in code

- AI coding agents will allow designers to work alongside devs, building the product directly in code

- This will require designers to develop new skills, learn new tools and develop a technical mindset

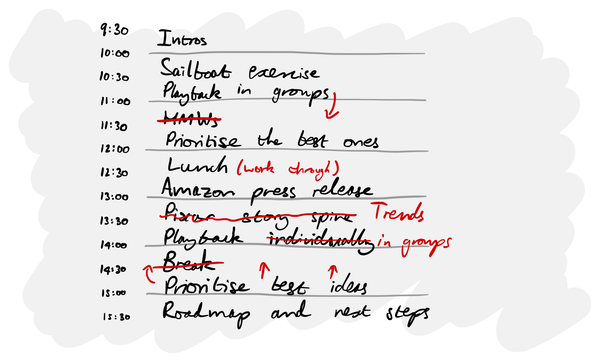

Before we get into the details, I want to be clear on one thing: I’m talking about how software gets made once you are ready to build the real production-ready thing. Product discovery isn’t disappearing, and with these AI coding tools it’s more important than ever.

AI coding agents are now good enough

With the release of Opus 4.5 and recent updates to Claude Code, AI coding agents are now capable of producing 100% of production code.

Of course using it to do this requires strict guardrails and structured processes, but in the right hands a single developer can do the work of ten people not using these tools.

Engineers are developing techniques to go even faster. Ralph Wiggum puts a coding agent in a loop where it can run for hours, persisting until it succeeds. Gas Town is a structure that gives agents different roles so that they can build software like workers in a factory.

Whatever concerns people have about code quality and security will melt away as methods are found to reduce these risks. And as Steve Yegge reminds us...

People still don’t understand that we’ve been vibe coding since the Stone Age. Programming has always been a best-effort, we’ll-fix-sh*t-later endeavor. We always ship with bugs. The question is, how close is it? How good are your tests? How good is your verification suite? Does it meet the customer’s needs? That’s all that matters. Today is no different from how engineering has ever been. From a company’s perspective, historically, the engineer has always been the black box. You ask them for stuff; it eventually arrives, broken, and then gradually you work together to fix it. Now the AI is that black box.

You need a design system in code before you can go fast

If you want to build software quickly with AI, you need to of course build the front-end as well as the backend. But unless you have your design system in code, the AI is going to be making all sorts of bad decisions about your UI and its implementation.

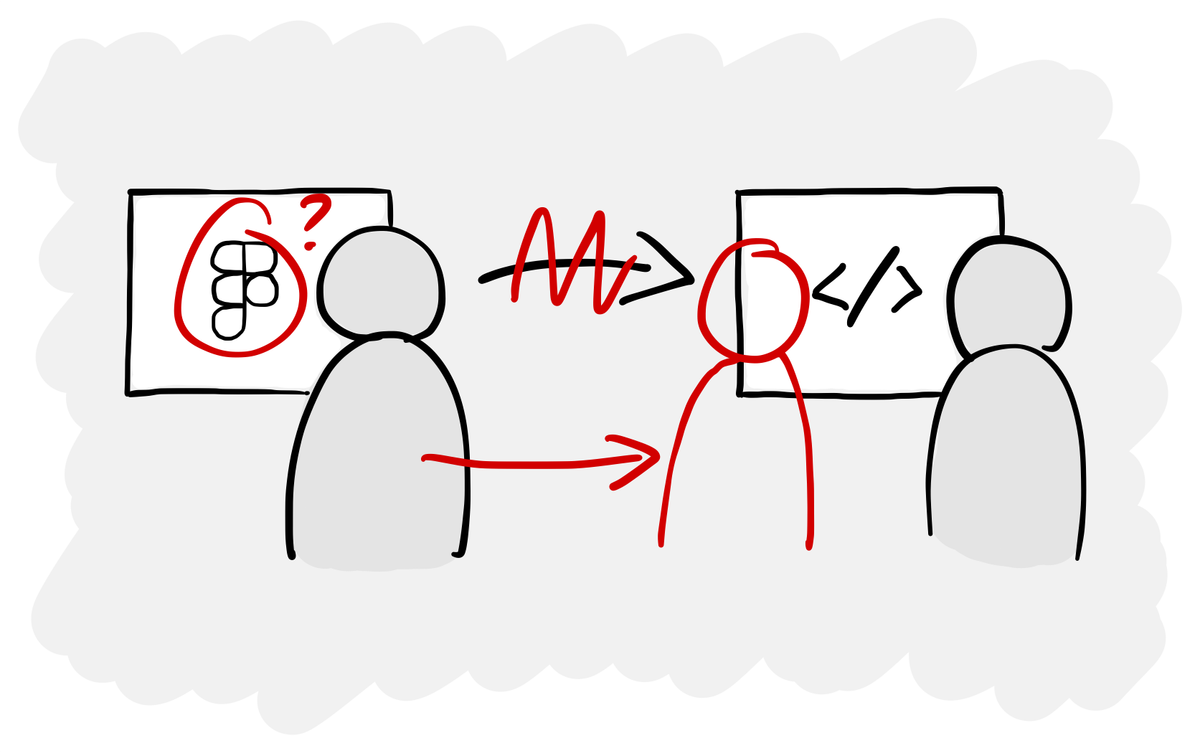

The problem is that unless you already have a robust design system in code (lucky you), it takes forever to create one if you start from scratch in Figma.

Most organisations’ processes assume that you create designs in Figma, then create a design system in Figma, then hand that over to developers to replicate it in code. This takes ages and leaves a lot of room for mistakes and misalignment. A button with all its variants might take a week to design and build.

Drawing pictures of screens in Figma and then handing over to developers to build acts as a handbrake on the whole process. And the faster developers can go, the less prepared everyone is going to be to wait around for design to do its thing.

Start in code, not in Figma

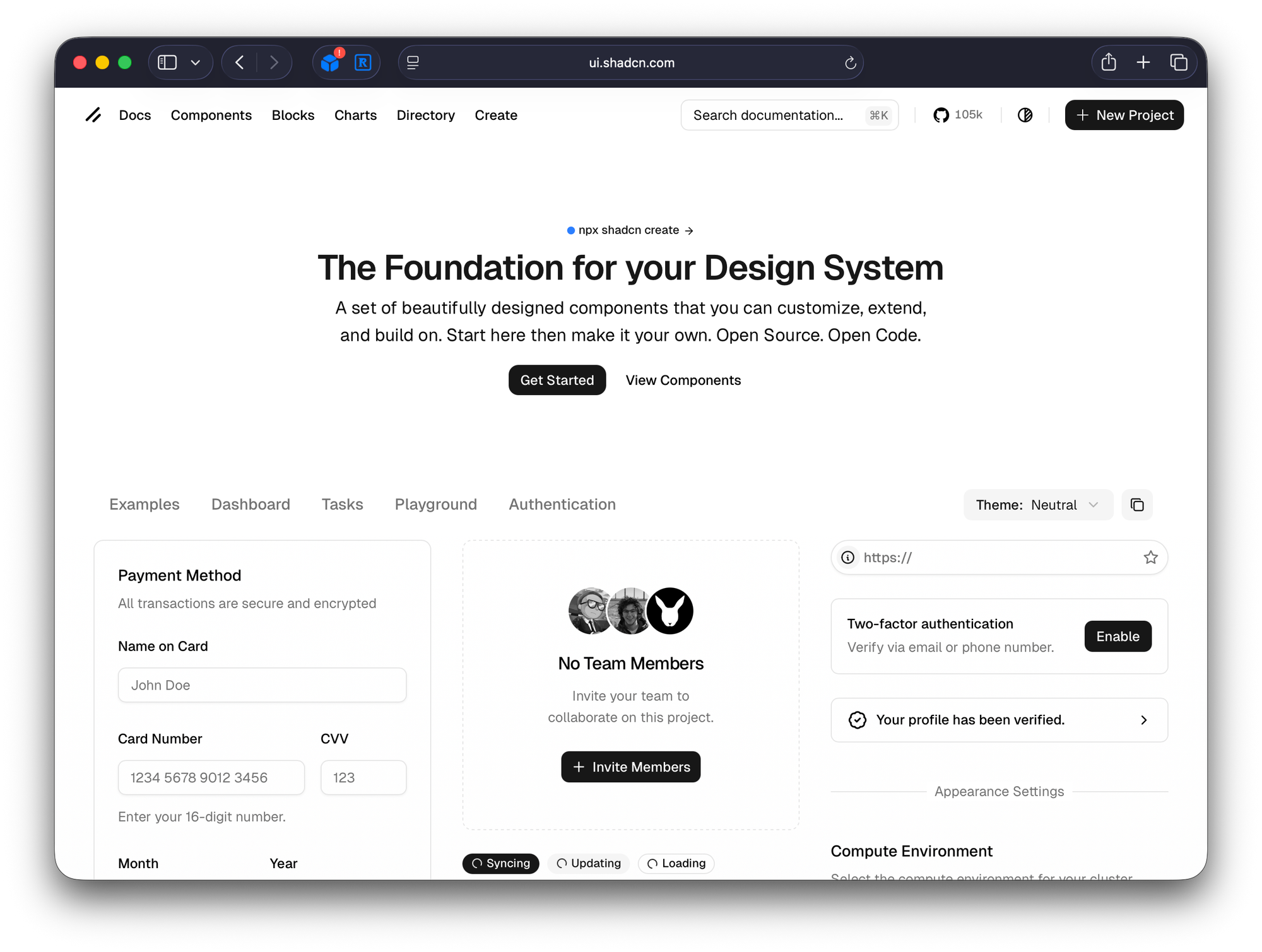

Therefore it makes a lot more sense to start your design system in code rather than in Figma. There are several libraries out there like shadcn that give you accessible coded components out of the box, which you can then style and extend as you please.

Type npx shadcn@latest create and you can have a coded library of components in your project in a few seconds.

Most software uses the same primitives, so why reinvent the button if you don’t have to? Starting in code also means there is no Figma-code gap or developer handover where things can get lost.

The designing-in-code tools gap

The only problem with starting in code is that the design tooling is very immature in this space.

You can set up Storybook to see what your components look like and how they behave, but if you want to design with your coded components on a canvas like you can in Figma, the options aren’t great. I’ve tried a couple of tools recently but they’re either very expensive and/or not refined enough.

Hopefully Figma will release some new features around this at their Config conference in the summer, continuing their trend of pushing it closer to code. In the meantime building, styling and using components isn’t something that every designer can easily do.

Now designers get to build the product

Current tool jankiness aside, the trend is clear. Designers won’t be writing code, but they will be working in and with code. Armed with tools like Claude Code, designers can build the product themselves, working alongside developers.

In the same way that Sketch and Figma lowered the technical barrier to designing software after Web 2.0 took web design beyond HTML, CSS and JavaScript, AI coding agents lower the technical barrier to building production software today.

When we look back in five years, the current way that software gets designed is going to seem absurdly wasteful. We essentially draw pictures of software and then hand them over to someone to build.

To work with code (again), designers need a different skillset

If your job changes from designing in Figma and then handing over to a dev, to sitting alongside them as a co-builder, you’re going to need skills such as...

- Basic technical skills and knowledge (e.g. how to use version control and GitHub)

- An understanding of how software gets built and the platforms used

- Breaking work into bite-sized tasks that agents can do successfully

- Writing precise instructions and constraints for coding agents

- Being able to spot when an agent is going awry or has misunderstood something

- The curiosity to learn new things and work in different ways

- Lack of fear of the terminal

I think a lot of designers and other UX folk like researchers will migrate to a more generalist ‘builder’ role where they can truly work on something end-to-end. You do the research, identify opportunities, generate and validate concepts with prototypes and then build the real thing.

Equally I think there will be plenty of room for designers who want to focus on the more visual execution side of things. AI isn’t great at creating a novel and differentiated brand and visual identity for a product. The UI it creates are good but don’t standout. When there’s more and more software being built, that’ll be increasingly important.

Collapsing the distance between intent and reality

If what I’ve written turns out to be true (and it may not be), we’ll see a significant disruption in how designers and developers work together, and in the tools they rely on to do that work.

While that might sound daunting, I think it’s something everyone involved in building products should be excited about. We get to remove points of friction in the process, particularly handovers, and work much more closely together around the real thing we’re building.

This future is an empowering one for designers. It places greater value on their judgement, taste and decision-making. When building becomes fast and cheap, the hardest problem isn’t how to make something, it’s deciding what’s worth making at all.