Yes, working through bureaucracy is your job

But good news: UX skills will help you do it.

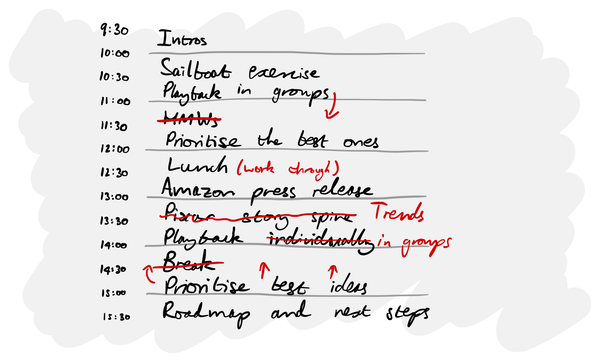

Ask any design leader what the least favourite part of their job is, and chances are that it’ll be getting new vendors onboarded, processing invoices, raising purchase orders and so on.

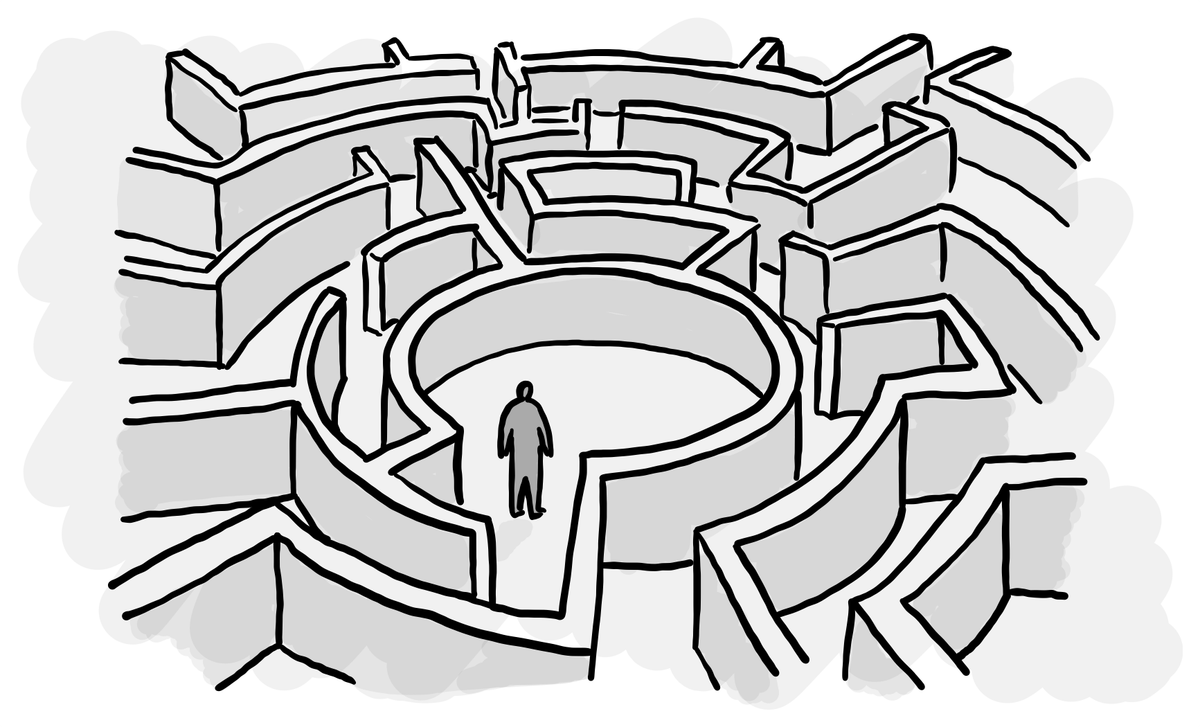

In many large organisations, these tasks can feel like an endless maze of bureaucracy. There are huge email chains, outdated systems and processes that no-one seems to have written down. It feels like these tasks take up too much time and get in the way of doing the ‘real work’.

The thing is, working with your organisation's bureaucracy is part of the job. Rather than complaining about it, we need to develop tactics for working through it effectively.

The good news is that as UX professionals, we already have many of the skills we need to get through these internal processes with as little stress as possible.

Why these tasks feel so painful

Bureaucracy is particularly frustrating for people in product, design and research roles because we see the world through the lens of user experience.

We have a high bar when it comes to interacting with organisations – including our own – and we’re able to spot every tiny thing that’s wrong with an experience. We’re especially sensitive to bad user experiences, and most internal processes have terrible UX.

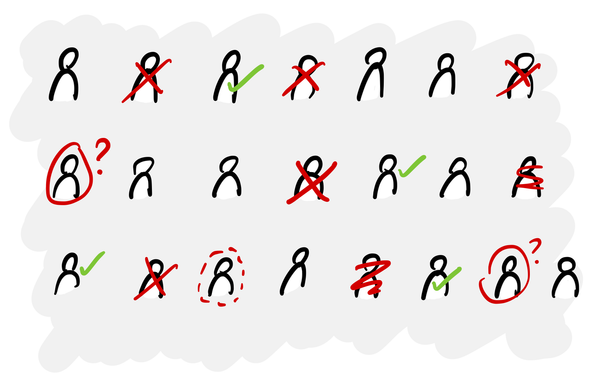

We’re also used to structured work environments where work is closely managed. In the software development process we have backlogs, prioritisation and systems to organise who’s working on what. When we ask another department to do something, we can fall into the trap of assuming that they operate the same way.

In reality, many departments don't work like this. Finance, legal and HR may just have a shared inbox. Tasks aren’t managed and prioritised in the same structured way as you would find in Jira. IT is usually the exception because they use ticketing systems, but most other departments don't.

Five ways to use your UX skills to get through the bureaucracy

Instead of getting frustrated, we can repurpose our professional skills to make bureaucracy more manageable.

Use empathy and curiosity

Rather than getting irritated when things don’t move as quickly as you’d like, use your research skills to try to understand the process and the challenges the people you're working with face.

How does their team actually work? What pressures are they under? A bit of curiosity and empathy can go a long way.

Be the project manager

Don’t just send an email to finance or legal and expect them to manage the entire process for you. If you want to move something forward, you may need to be the project manager of that task.

If nothing seems to be happening, send weekly status updates to everyone involved, summarising where things stand. This is incredibly helpful because people often can't remember what a long email chain is about and they have 50 other similar requests to deal with.

You can use AI to summarise the one or multiple threads about a task, which is especially useful when new people get added. Being the person who keeps people aligned and on track can move things forward.

Visualise the process

Journey mapping isn’t just for ‘the real work’ – it’s valuable for internal processes too. Often, the process hasn't been visualised by the team themselves, so it’s actually quite a helpful artefact for them.

When you draw a diagram of your understanding, it’s much easier for stakeholders to spot gaps and quickly tell you how things really work. Visualising something helps expose your assumptions about how the process works.

I recently had to agree a new approval process with our finance team. Instead of back-and-forth emails about which documents would be required, I created a mock email in Miro with example text and little icons for each attachment, including screenshots of what each item would look like. Visualising it helped everyone understand how the process would work and we got agreement on it much more quickly.

We often forget to apply our design skills when communicating with people internally who aren’t usually our stakeholders in the design process.

Don't wait for permission

You might be worried about stepping on people’s toes or disrupting processes, but as long as you do things in a helpful and positive way, using your skills can speed things up and make the whole experience more pleasant for everyone working on it.

You don’t need to ask permission to draw a diagram of how something works, and you don’t need permission to be the one who summarises the email chain.

Your role in whatever task you are doing can be emergent: the ‘project manager’ is whoever is doing the project management, just as the ‘leader’ is whoever is doing the leading.

Obviously, if you want to change how a process works, you need buy-in from people. But if you’re just working through a process and managing a task that you care about, you generally have the freedom to push that task forward using your skills in any reasonable way.

Document the pain for others

If you have to go through a painful bureaucratic process, documenting it can help those who come after you.

I once had to navigate a laborious 30+ step process to get set up on a client’s IT systems. The instructions from their IT department weren't comprehensive (to say the least), so I documented the whole process in Notion with screenshots. My colleagues were then able to go through the same process much faster than I did.

You don’t have to change the process to make it easier to work through – just documenting it for others is enough.

It’s part of the job

As UX professionals, we love to improve the way things work, but sometimes you just have to accept a cumbersome process and get through it the best you can.

If you tried to improve every process you encountered, you’d never get your day job done.

More often than not, you can’t change the process, but you can work through it in the best way possible for yourself and the people you’re working with.

The skills we use every day – making sense of things, visualisation, documentation, project management, empathy, and problem-solving – are incredibly valuable for navigating internal bureaucracy. We just need to remember to apply them beyond our immediate work and use them to make our own – and our colleagues’ – lives easier.