Why everyone’s talking about ‘taste’ as the next differentiator

Human expertise and judgment is making a comeback.

There's a word that keeps cropping up in Silicon Valley commentary lately: ‘taste’.

You hear it on podcasts, read it in articles and see it on LinkedIn. The idea is that if anyone can use AI to create software, then your differentiator isn't technical skills, it's taste.

"In a world of scarcity, we treasure tools. In a world of abundance, we treasure taste. Everyone's software is good enough. Software used to be the weapon, now it's just a tool... Taste is the new weapon."

"In the Age of AI, Technical Founders Are Overrated. Taste Is the New Tech Stack... AI has turned the 40-hour work week into 40-minute tasks. In an era where code is no longer scarce, by definition, technical skills are no longer special."

Krithika Shankarraman, former VP of marketing at OpenAI, on Lenny's Podcast:

"Taste is going to become a distinguishing factor in the age of AI because there's going to be so much drivel that is generated by AI... truly, the companies that are going to distinguish themselves [are the ones that show their craft]."

For each trend, there is an equal and opposite trend

Now that the barrier to creating software has been lowered dramatically, anyone with enough determination can start a software business in a weekend, even without coding skills.

But what AI doesn’t have is ‘taste’.

It doesn't have enough context or judgment to determine what quality looks like. This is a trait that only humans have.

If anyone can create software, then what's valuable isn't who can build the thing anymore, but who can build the right thing, for the right people, in the right way.

Taste is expertise in disguise

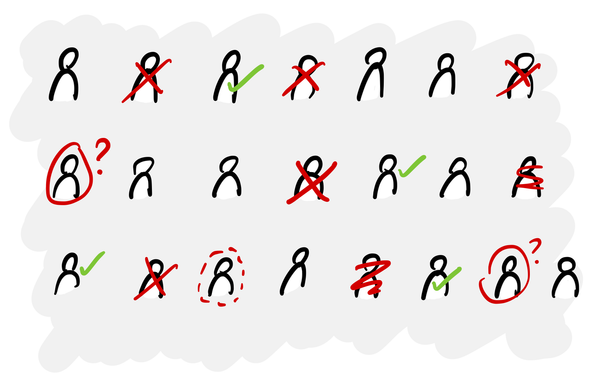

The way taste gets talked about is on a spectrum. On one end, it's portrayed as rare genius that only a select few possess, like having an eye for design that can't be taught. On the other end, it's framed as a learnable skill you can develop through experience and practice.

I think it's the latter: taste is just expertise in disguise.

When you make decisions without data – which you do constantly – you're drawing on everything you've learned, seen and understood about people. That accumulated knowledge helps you predict what others will find engaging, useful or beautiful.

Every time you write an email, make a design decision or choose how to present information, you're using your taste. You're using what you've seen work before to anticipate what will work in the future.

Opinion vs. data

It’s easy to recoil at the trend of putting subjective opinions on a pedestal. After a decade of being encouraged to make decisions based on data and evidence, now we’re meant to abandon that and use our intuition?

Some of the biggest product failures have come from leaders who believed their own genius, which is why we all groan about HiPPOs (the highest paid person's opinion).

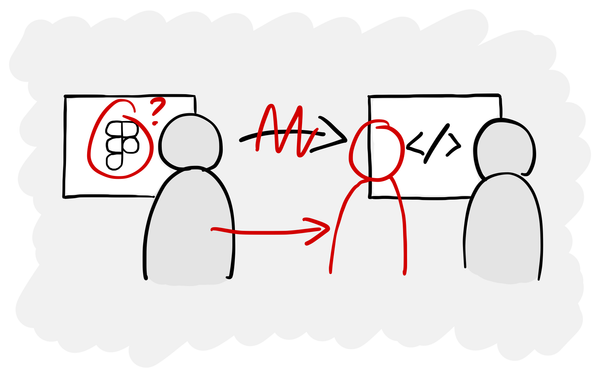

It’s a fair critique: we shouldn't abandon evidence-based decision-making in favour of pure intuition. But we also can't dismiss the value of accumulated expertise. The best outcomes come from blending both approaches:

- Use data and research to understand user needs and validate assumptions.

- Use your expertise to make the thousands of micro-decisions that data can't answer.

Who benefits from the taste trend

The focus on taste is increasing the perceived value of those who understand users and how to design for them. The $6.4 billion OpenAI is paying for Jony Ive's agency, LoveFrom, which employs around 50 people, is one data point for this.

Another thing I hope comes from designers' intuition being valued more is that they get more permission to be creative and take risks.

The recent Airbnb redesign hints at this shift. Even though it’s not revolutionary, the skeuomorphic icons and motion design have garnered a lot of attention. If you look at software from 20-30 years ago – think about WinAmp or early skeuomorphic design in iOS – there was so much more playfulness. Today's interfaces often feel sterile and lifeless.

Finding a balance between instinct and insight

The rise of taste as a differentiator shouldn't be about abandoning rigorous product development. It should be about recognising that in a world where the technical barriers are lower, human judgement and expertise become more important.

Good taste isn't magic – it's pattern recognition developed through years of experience. The people who will thrive are those who can combine their accumulated expertise with solid research and data.

After all, taste without validation is just opinion. But data without human interpretation is just noise. The future belongs to people that can do both.